Letters from Army chaplain killed in Korea reveal a life of heroic service

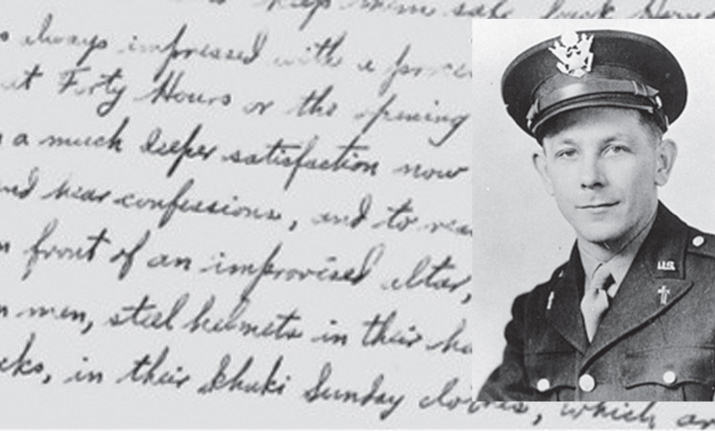

The handwriting of U.S. Army chaplain Father Herman G. Felhoelter, OFM, is seen in an excerpt from a letter to the Biggs family, members of St. Boniface Parish in Peoria. The letter, dated Feb. 25, 1945, was penned in France and tells of his ministry to soldiers during World War II. Father Herman would be killed five years later while tending to wounded soldiers on a battlefield in Korea.

By Alexis Lavin

EDITOR’S NOTE: The author is an adjunct professor of history at Illinois Central College and a volunteer at the Archives of the Diocese of Peoria.

When I tell my students that history is fascinating, I am usually confronted by distinct expressions of disbelief. The majority of them think that history is boring, that it’s just a set of dates and lists of people and places that mean nothing to them. As a historian, of course I disagree while acknowledging that sometimes that can be the case.

Often, history is boiled down to basic statistics and this is particularly true when warfare is examined. Events like Gettysburg, the Somme or Herrlisheim are reduced to dates, places, and casualty numbers. Perhaps this is because these details are easily digestible, but it is also because simply focusing on numbers prevents — and protects — us from realizing the full horror of armed conflict. However, sometimes we are given the opportunity to peel back the curtain of generalities and to truly understand what life was like for those who experienced these events firsthand.

Through the generosity of Jody Ricca Shelton of St. Charles, Missouri, the Archives of the Diocese of Peoria was blessed to receive copies of 93 letters written by a Kentucky-born Army chaplain who, prior to his enlistment, served at St. Boniface Church (today’s St. Ann) in Peoria.

DIDN’T CONSIDER HIMSELF A HERO

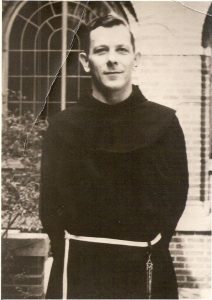

Like so many of his generation, Father Herman G. Felhoelter, OFM, didn’t see himself as a hero. Not when he volunteered to join the Army as a chaplain in 1944; not when he boarded a troop ship for a long, dangerous journey to England; not when he ministered to the men of the 12th Armored Division — the famed “Suicide Division” — as they fought mile by bloody mile through France until they finally reached Nazi Germany.

Fr. Herman served as an assistant at St. Boniface Parish in Peoria from February 1943 to March 1944. Copies of 93 of his subsequent letters to the Art and Emma Biggs family were recently gifted to the Archives of the Diocese of Peoria.

And not in 1950 when he knelt among 30 wounded American soldiers in Korea, totally unarmed, as North Korean soldiers bore down on them.

He didn’t see it — but those around him did, particularly the Biggs family on Peoria’s South Side who had known Father Herman when he had been at St. Boniface Parish in 1943 and with whom Father kept up faithful correspondence between 1944 and his death in 1950.

The Biggs family — parents Art and Emma and their two children, known affectionately as Jody and Artie — were parishioners at St. Boniface and became Father Herman’s close friends during his time in Peoria. His letters to them are filled with humor, anxiety, encouragement, frustration, and gratitude.

Above all, they are filled with his deep faith and trust in God. In spite of the horrors he witnessed, the privations he experienced, and the doubt that sometimes crept in about what he was doing, Father Herman never lost his faith that he was where God wanted him to be.

“I NOW KNOW WAR IS HELL”

What is most striking in the letters is that Father Herman — this man to whom so many came with their problems, fears, and concerns — unburdened himself to the Biggses, knowing that everything he told them would remain between him and his friends. He spoke of his homesickness for Peoria, his frustrations with Army life, the courage of the men around him, and — perhaps most poignantly — his wish that God’s plan for his life had been to serve in a parish, rather than in the military. How often were similar feelings expressed by the men to whom Father was ministering — just wanting to be home with those they loved and away from the horror and filth of battle.

Father Herman never got graphic in his descriptions of his experiences. He frequently mentioned the censors as the reason, though his letters also give the impression that he didn’t share details because he didn’t want to talk about the harsh realities of war. In one letter, dated Dec. 28, 1944, Father said: “I have often read about this war and what it means, and I had often visualized myself writing a glowing account of my experiences. But I’ve changed my mind . . . I now know what war is — and it is hell.” In another letter, dated June 13, 1945, he enclosed a map for the Biggses to hold onto for him. The map, from January 1945, is “very clear to me . . . But there is a story behind . . . that I am trying to wipe from my memory. I saw too much, there. . .”

Unfortunately, we do not have the map itself. However, according to Bill Lenches — a historian attached to the 12th Armored Memorial Museum in Abilene Texas — in January of 1945 Father Herman’s division was involved at Herrlisheim — referred to as the “Little Bulge” — for 13 days. During much of this time, Father was probably assigned to Purple Heart Lane, a road out of the embattled town that had been chosen by the Field Surgeon as his triage area. It was a period of brutal, bloody fighting during which 10,000 Allied soldiers were facing around 70,000 seasoned Nazi troops.

A LIFE OFFERED IN SERVICE TO GOD, OTHERS

For his bravery during this and subsequent engagements, Father Herman was awarded the Bronze Star. He wrote to the Biggses informing them of the honor on June 13, 1945 but emphasized that it was to remain “just between us.” Five days later, he wrote and said: “Concerning the bronze star stuff, you can do what you want. But I’m not telling you anything. But I mean this: The only ones that deserve any credit are the guys that aren’t coming home.” It was one of the only times in his extensive correspondence that Father sounded abrupt — one can only imagine what he was feeling as he wrote home.

“I was always impressed with a procession in Church . . . But it is a much deeper satisfaction now to sit on an old box and hear confessions, and to read the Sunday Gospel in front of an improvised altar, to a group of unshaven men, steel helmets in their hands and guns on their backs . . .”

He, like his brothers in arms, had his shadow moments. Yet he always turned back to the light of faith, finding real joy in the work that he was doing. In February of 1945, he wrote:

“I was always impressed with a procession in Church . . . But it is a much deeper satisfaction now to sit on an old box and hear confessions, and to read the Sunday Gospel in front of an improvised altar, to a group of unshaven men, steel helmets in their hands and guns on their backs . . . They listen just as they used to do back in the parish church each Sunday morning. They and I both know that we are offering the same Christ that we did back [home] . . . And that makes it possible to bear — the knowledge that if I were not here, possibly there might be one less priest with [them].”

His letters are truly a testament to a life offered in service to God and to others.

HE STAYED WITH THE WOUNDED

At no time was that clearer than through his actions during the Korean War. After leaving active service in 1946 with the rank of Captain, Father volunteered to return to the Army in 1947, once again feeling the call to minister to soldiers in harm’s way. After war was declared in 1950, he was deployed to Japan that spring with the 19th Infantry Division. His last letter to the Biggses was dated May 16, 1950. He ended with yet another request for a letter and said, “I will remember the fine time I enjoyed [with you] in February. Just like way back when. You people surely are fine. No kidding.” On July 12, Father Herman and the 19th engaged with North Korean troops at the Battle of Taejon.

Four days later, Father was with approximately 100 men from his division who had with them 30 wounded, including men borne on litters who were too severely wounded to walk. The weary soldiers climbed to the top of a mountain before it was determined that the seriously wounded on litters could go no farther – the litter-bearers were exhausted. The medical officer, Captain Lipton J. Buttrey, chose to stay behind and Father Herman and another chaplain, a Baptist minister, flipped a coin to see who would stay. Father Herman won and remained with the wounded. The hope was that another group of troops would come along to help move the men on litters. Unfortunately, they were found by enemy soldiers first.

When they heard North Korean forces approaching, Father Herman told Captain Buttrey to run, that he would stay with the wounded. The North Korean troops began firing and, though severely wounded in the ankle by enemy fire, Captain Buttrey was able to get away. Father Herman continued administering extreme unction to the injured in his care even as North Korean troops flooded the area.

In spite of being unarmed and his status as a non-combatant, Father Herman was executed as he knelt amongst his men. All 30 critically wounded soldiers were also murdered before the North Korean troops withdrew. It was July 16, 1950 — one day before Father’s 37th birthday.

For his sacrifice and gallantry, Father Herman Felhoelter — the first American chaplain to lose his life in the Korean War — was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Purple Heart. His mother — who had also suffered the loss of her son, Bill, in World War II — wrote of a letter she had received four days before Father Herman died in which he said: “Don’t worry, Mother. God’s will be done . . . I am happy in the thought that I can help some souls who need help.”

A COMMON THREAD THROUGH THE LETTERS

Father Herman spent almost a quarter of his religious life ministering to soldiers in conditions and situations that are beyond our imaginations. He sacrificed himself while ensuring that those souls in his charge would not meet the enemy unsuccored. This spirit of selflessness and of resignation to the will of God is an unbelievable grace and I am privileged to have been given the opportunity to transcribe and catalogue Father Herman’s letters. They contain the gamut of experiences but one thread links all of them together and gives the reader a full picture of the man that wrote them — the glory of a soul that, while still struggling, has submitted itself to the beauty of God’s plan.

Father Herman tells us the wonder of it himself when he said in a letter just after Christmas of 1944, “I am no longer homesick . . . most of the time I’m glad to be here, because I know that if I were a soldier I too would want to see a priest once in a while to bring Christ to me. And I thank God that I have the privilege.”