Full text of homily at Founder’s Day Mass recalling Bishop John Lancaster Spalding

Canon J. J. Flattery of Danville recalls the life and accomplishments of the Diocese of Peoria's first bishop, John Lancaster Spalding, during his homily at the Founder's Day Mass on Aug. 25. (The Catholic Post/Jennifer Willems)

EDITOR’S NOTE: Following is the full text of the homily given by Canon J. J. Flattery of Danville at the Founder’s Day Mass celebrated at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Peoria on Aug. 25, 2016. The Mass marked the 100th anniversary of the death of Bishop John Lancaster Spalding, the founding bishop of the Diocese of Peoria, and the completion of a major restoration project at the cathedral.

Bishop Jenky, brother priests and deacons, Sisters in Christ, Christians all:

Today is the day the Lord has made, let us rejoice and be glad.

We have gathered here today in this historic cathedral of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception to remember John Lancaster Spalding, the first bishop of Peoria, on the centenary day of his death and to celebrate the completion of the restoration of the cathedral he built.

We have all thrilled to stories about Pere Marquette and Louis Jolliet sailing down the Mississippi and up the Illinois rivers in 1673 to bring Christianity for the first time to this area when it was a part of new France. But to get to the American roots of John Lancaster Spalding we must go back 39 years earlier to the Maryland shore of the Chesapeake Bay. There, on March 25, 1634, the feast of the Annunciation, the passengers on the Ark and the Dove, Catholics and a few Protestants, landed to establish a new and unique third English colony. Under the governorship of Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore, this new colony of Maryland was to have the precious right of freedom of religion for Catholics and for Protestants alike. This is the precious legacy of the Ark and the Dove.

At that time in much of Europe there was the territorial imperative cuius regio, eius religio (whose region, his religion). Not so in this new English colony of Maryland. Here there would be religious freedom for all. Later, impaired for a time under the tyranny of Oliver Cromwell and the English Penal Laws, this precious religious freedom was kept alive and vibrant in the hearts and minds of all true Marylanders.

In the great expedition of Marylanders to Kentucky in the 1780s, they carried with them this precious legacy of the Ark and the Dove.

TWO GREAT ENGLISH CATHOLIC FAMILIES

From these daring pioneers of religious freedom came two great English Catholic families that contributed so much to God and country in America: the Carrolls of Maryland and the Spaldings of Kentucky.

Prominent among our founding fathers were the Carrolls. Catholics at that time numbered less than 40,000 in a colonial population of 4 million. Charles Carroll of Carrolton signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. His cousin, Daniel Carroll helped draft and then signed the Constitution of the United States in 1787 and his younger brother, John Carroll, was consecrated the first bishop of the United States on the feast of the Assumption on Aug. 15, 1791. That same year Daniel Carroll worked closely with James Madison to guarantee that precious gift of the Ark and the Dove, freedom of religion, was embedded in the first amendment in our Bill of Rights.

The Spaldings had come west from Maryland to central Kentucky. There, in Lebanon, John Lancaster Spalding was born on June 2, 1840, the son of Benedict and Mary Jane Lancaster Spalding, the first of nine children. In his early years he was known as Lanc.

Lanc was home-schooled by his mother who was probably his greatest teacher because she awakened in him a pursuit of truth and excellence which never wavered across his life span. She gave him a sense of place and family. Among her ancestors was Edward III of England (House of Lancaster). She also taught him about the legacy of the Ark and the Dove.

By the time that Lanc was 8 years old, under President James Polk, America stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from sea to shining sea. Manifest Destiny and American Exceptionalism were simply part of his growing up in America. He saw the American experiment in self-governance with its checks and balances between the legislature, the executive and the judicial as a beacon of freedom for all mankind. He truly loved and treasured this democratic republic and all its citizens.

A YOUNG PRIEST’S REPUTATION GROWS

Inspired by his uncle, Bishop Martin John Spalding, Lanc aspired to become a priest. He crossed the Ohio River to enter Mount St. Mary of the West. From there he went to the American College of Louvain where he was ordained on Dec. 19, 1863.

After ordination he stayed on for further study at Louvain, then in Germany and finally at Rome. He returned to America in May 1865, one month after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

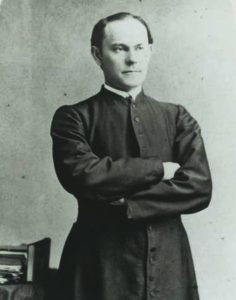

111 – Father John Lancaster Spalding

Back in Louisville, he was an assistant at the cathedral and secretary to the new bishop and later chancellor. In 1869 he established St. Augustine Parish in Louisville for the newly-liberated black Catholics and served as pastor.

Unexpectedly in 1872, his uncle Archbishop Martin John Spalding of Baltimore, now in the primatial see of John Carroll, died. He had left all his papers and documents in the hands of Father Isaac Hecker, a convert priest and founder of the Paulist community. Young Father John Spalding was deemed most fitting to write the biography of his uncle and so he left Louisville and went to the Paulist Mother House on 59th Street in New York where he took up residence.

After completing the biography, Father Spalding stayed on in New York at St. Michael Parish on 9th Avenue and 32nd Street where Father Arthur Donnelly was pastor. Soon he was in charge of the schools of the parish. He also had the opportunity to preach and lecture widely while at the same time writing essays and publishing books. His reputation spread far and wide. There was little surprise when he was selected to be the first bishop of Peoria, Illinois.

THE FIRST BISHOP OF PEORIA HAD A VISION

On May 1, 1877, in old St. Patrick Church on Mott Street in New York, he was consecrated bishop by Bishop John McCloskey of New York, Bishop James Gibbons of Richmond and Bishop Thomas Foley of Chicago. His old rector from Mount St. Mary of the West, now Bishop of Columbus, preached the sermon.

From New York, the new bishop entrained for Chicago where Bishop Thomas Foley came aboard and accompanied him to Peoria where he would install him as the new bishop. The whole city turned out to greet and welcome him. The two bishops rode together from the station for the installation at St. Mary Church, the new cathedral.

After all the welcomes and ceremonies and speeches were over, imagine the young bishop, just shy of his 37th birthday, sitting down at his desk with a map of his diocese covering some 17,000 square miles. In three years five more counties — Rock Island, Henry, Bureau, Putnam and LaSalle — would be added bringing it to more than 18,500 square miles.

He had a horse, a buggy and a nearby train. The roads were often mired in mud. There was no electricity in his house or church. No telephone on his desk. Nearby was a telegraph office. Quite a different world.

But he had a vision for the diocese and beyond that would guide him across the years. To assist him in his mission he had some 51 priests in some 70 parishes to care for about 40,000 people, mostly Irish and German at the time.

He immediately set about recruiting priests for the diocese. His first was his brother Benedict who came with an exeat from the diocese of Louisville. He would become rector of the cathedral and chancellor.

Next he made contact with the Franciscans, Capuchins, and Benedictines who graciously sent priests. On July 16, 1877, Mother Xavier Termehr and her community, refugees from the tyranny of Bismarck’s Kulturkampf in Germany, came to Peoria to become the Third Order of St. Francis of Peoria and staff St. Francis Hospital. He also was able to obtain a number of German priests and other sisters fleeing the same persecution and enlist their ministry as pastors, teachers and hospital staffers.

A DIFFICULT PERIOD FOR CATHOLICS

It is hard for us today to comprehend how poor and uneducated and vulnerable were the 40,000 faithful in this diocese when he arrived. Most had come to America with nothing and now they found themselves at the bottom of the society. They were canal diggers, railroad builders, miners and small shop keepers often with families who were easily exploited.

We should never forget that as late as 1945, 65 percent of Catholics in America were in the lower social economic strata of our American society. Few had the opportunity to go to college. The GI Bill was for them a gift of God. For the first time college doors were opened to a large number of Catholics. Just remember for a moment how many priests of this diocese used that same GI Bill for their entry into a seminary.

It is also hard for us today, in a somewhat more ecumenical age, to realize how deep and pervasive was the hatred and distrust for Catholics in most parts of America. Bishop Mark Hurley has treated the depth of this bigotry in his book “The Unholy Ghost: Anti-Catholicism in the American Experience.” It was and often still is the “Persistent Prejudice in America” as Michael Schwartz called it in his book.

Twice in the lifetime of Bishop Spalding, beyond this habitual prejudice, political parties were formed to outlaw and destroy the Catholic Church in America; the Know Nothing Party of the 1850s and the American Protective Association of the 1890s.

Such were the circumstances facing the new bishop and his flock. The bishop had a vision for a better America not only for the Catholics of his diocese but for all Americans.

EDUCATION AT THE CENTER OF HIS ENDEAVORS

Already in June 1878 Bishop Spalding was the speaker at the 34th Annual Commencement of the University of Notre Dame. There he began to lay out a program to address the social evils of the time. In no way was he satisfied with the status quo. His analysis was broad and called for equality and education for women, the end of child labor, better working conditions for laborers and, above all, education at all levels.

Education was always at the center of all his endeavors. He was constant in his call for parish schools in order to open the minds of children to God and the opportunities of life. Jesus had said: “I have come that you may have life and have it more abundantly.” Bishop Spalding wanted that abundant life for all. He sought to give men and women, boys and girls, the opportunity for a better life where they could serve God and be good citizens of this American democratic republic that he so loved.

For him Catholic schools were essential. “The church cannot consent to the exclusion of religion from any educational process. When our common schools system was finally organized as exclusively secular, nothing was left for Catholics to do but to build and maintain schools of their own in which (the) will, the heart and the conscience as well as the intellect, should be educated.”

Frequently, he praised the Catholic people for the sacrifices that they made to maintain their schools.

He regarded Catholic schools so highly that he made this dire prediction: “Without parish schools there is no hope that the church will be able to maintain itself in America.” Does that prediction not give us pause?

He would often speak about the need for the education of women and the right of a woman “to upbuild her being to its full stature, to learn whatever may be known, to do whatever right things she may find herself able to do.” This too was part of his vision.

He felt the church was most responsible when it was actively involved in social concerns. The priest must “go forth into the great world that is controlled by opinion, dominated by aims and ideals, which it is his business to bring more and more into harmony with the truth and love revealed in Christ.” That is why the priest must be highly educated.

Msgr. John A. Ryan, who did so much to improve the conditions of the working man in America in the early 20th century, graciously acknowledged his debt to the thought of Bishop Spalding. Ryan wrote: “For many years he executed a greater influence upon my general philosophy, my ideals, my sense of comparative values than any other contemporary writer . . . . . I like to think that his intellectual sympathy with the economically weak and the understanding of the efforts made on their behalf . . . . were the natural outcome of his ideals.” Msgr. Ryan also recognized that Bishop Spalding had first introduced the concept of a living, family, saving wage as a postulate of justice.

Our own John Tracy Ellis perhaps best took the measure of John Lancaster Spalding in his short biography when he gave him the title “American Educator.”

In everything he did, his sermons, lectures, essays, books, he was always the teacher.

CATECHISM, CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY, CATHEDRAL

He was also quintessentially American. With his roots in the Ark and the Dove, he was proud of his English family, thoroughly Americanized. He himself was a seventh generation American.

When some of his enemies, especially in the APA, challenged his loyalty as a Catholic to America, he could point out in a withering way that his ancestors were among the Founding Fathers while their ancestors were still back in some obscure villages in Europe longing to come to America.

He played a major role at the III Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884, helping to draft and publish the first Baltimore Catechism, pressing for the legislation to require each parish to have a parish school. He also helped in forming a committee of archbishops to consider the idea of a seminarium principale, a high school for priests where they could be educated beyond the limited scope of the seminary. This would eventually become the Catholic University of America. When the cornerstone was laid four years later on May 24, 1888, Bishop Spalding spoke to a great crowd there that included President Grover Cleveland, members of his cabinet and some 30 bishops.

Back home he presided over his diocese with a light hand. He wrote: “The tendency of good government is to make government unnecessary.” At a diocesan synod he told his priests: “If a pastor is not a Bishop in his own parish, it is his own fault.”

Archbishop Patrick Ryan of Philadelphia is on record as saying, “Bishop Spalding has the best administered diocese in the country.”

When Bishop Spalding had arrived in Peoria in 1877, he had a small grayish, one-story church located on Bryant and Jefferson — old St. Mary. Almost from the beginning he told his people that he had a vision for Peoria, for the diocese and a new church. Finally, on May 15, 1885,the cornerstone for that new church was laid.

He told the people then that “this church shall be the center of light and power and unity. This church will be built solidly, symbolizing the power and enduring life of the religion given to man by Jesus Christ.”

Four years later, on May 15, 1889 amid pomp and pageantry and marching bands, with the twin spires jutting 200 feet skyward, the mighty doors of the new cathedral were thrown open to admit the rejoicing people and clergy. The mighty organ thundered the glory of God amid a huge chorus of harmonious voices as Bishop Spalding accompanied by two archbishops and 80 priests and a great throng of people entered the cathedral to celebrate the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

Above the altar in the new cathedral was an oil painting of the crucifixion which was brought from old St. Mary. It is still there today — what a beautiful symbol of continuity!

Just days after the great dedication Bishop Spalding signed an agreement on June 5, 1889 with the Benedictines to come to Peru and establish St. Bede Abbey to honor the great English Benedictine historian Bede and open a school of opportunity for the area.

THE PHANTOM HERESY

The 1890s were not the happiest times for the church in the United States. Bishops and archbishops at times quarreled publicly over differing approaches to schools and other social problems. Amid this internal disarray came the savage external atttack from the American Protective Association which sought to belittle and destroy the church.

Differing and often damaging reports flooded into Rome about the condition of the church in America. Finally, Pope Leo XIII determined to send an apostolic delegate to be his eyes and ears on the scene, his representative in America. Many bishops, including Bishop Spalding, felt this was inopportune because of how it would be interpreted by Protestants and especially the hostile APA.

Shortly after the death in 1888 of Father Isaac Hecker, the founder of the Paulist Fathers and friend of the Spaldings, Father Walter Elliott, a Paulist himself, wrote a biography “The Life of Father Hecker” in 1891.

When translated into French in 1898, Abbe Felix Klein wrote a rather intemperate preface. The translation further exaggerated both the aims and the methods of Father Hecker and in some cases carelessly expressed them.

The translation immediately became mired down in French politics. More adverse reports flowed from France to the Vatican about this supposed Catholic Church in America.

Then on Jan. 22, 1899, Pope Leo sent a letter (Testem Benevolentiae) to Cardinal Gibbons condemning certain teachings that he had heard about in America. Cardinal Gibbons wrote back circumspectly that there was no such teaching in America.

Bishop Spalding, on the other hand, went to Rome in early 1900 and requested and received an audience from Pope Leo. Quickly the subject of Americanism came up. The bishop spoke boldly to power when he told the Holy Father that no such errors were taught or believed in America.

When the subject of Father Hecker came up, Spalding simply asked the pope, “Did you know Father Hecker?” When the pope replied in the negative, Bishop Spalding said, “I did and a better Catholic we never had.” Then he added, “I knew Father Hecker well and intimately, and he was a holy, zealous and enlightened priest. I am certain that he never believed or taught what they accuse him of.”

Slowly the whole brouhaha of Americanism, the phantom heresy, as it was called, faded into the dust bin of history.

Today, the cause for the canonization of this same Father Isaac Hecker is moving forward in Rome.

CELEBRATING SILVER JUBILEE, GROWTH

Perhaps the happiest moment in the life of John Lancaster Spalding occurred right here in this cathedral when on May 1, 1902, he celebrated the Silver Jubilee of his consecration as bishop and also the Golden Jubilee of the cathedral parish.

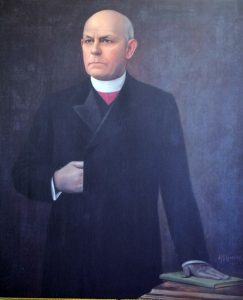

This portrait of Bishop Spalding is dated 1907, a year before he resigned as Bishop of Peoria.

In the procession to the cathedral there were 250 priests, an abbot, 16 bishops, 4 archbishops and James Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore, the successor of our first American bishop, John Carroll.

Bishop Spalding celebrated the Pontifical High Mass and the cardinal preached. Toward the end of his talk he mentioned his close relationship to Martin John Spalding whom he called “his father in God” and also his being one of the consecrators of Bishop Spalding 25 years ago.

He then added that Bishop Spalding had applied his talents not only to the growth of his own diocese but also for the enlightenment of his fellow citizens across the land.

He also praised the loyal and devoted clergy and the generous cooperation of the laity — a triple alliance, he called it, upheld by the enduring power of divine love.

At the banquet later, Father Keating, pastor of St. Columba in Ottawa, spoke about the growth of the diocese under Spalding to some 120,000 Catholics, 181 priests, 214 churches, 3 academies for boys, 9 academies for girls, 61 parochial schools, 2 orphan asylums and 7 hospitals.

In this cathedral again that evening at Vespers Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul said: “Twenty-five years in the episcopate . . . without stain or blemish . . . that is what we praise today. The whole Church of America owes to Bishop Spalding a singular debt of gratitude and to pay this debt bishops and priests have congregated today in Peoria from all parts . . . of the continent. Bishop Spalding, ad multos annos!”

Later that year President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to the national arbitration board to settle a terrible coal strike in Pennsylvania involving some 197,000 miners. The commission began in November 1902 and went on until March 1903. Bishop Spalding again showed his deep concern for all but especially the working man.

SUFFERS STROKE IN 1905, CELEBRATES GOLDEN JUBILEE

Amid his busy schedule came the feast of the Epiphany on Jan. 6, 1905, and the terrible stroke from which he never fully recovered. He finally tendered his resignation to the Holy Father on Sept. 21, 1908. The pope accepted it and gave him the title of titular Archbishop of Scythopolis.

Later, reflecting on his stroke he wrote: “I was intoxicated by my work and God struck me down.” The priests of the diocese gave him a little house on the hill for his retirement — the famous Glen Oak residence.

He had a bright moment in 1910 when the retired President Roosevelt came to Peoria to speak at the annual Columbus Day banquet as the guest of Archbishop Spalding.

When TR arrived, he “bounced off the train and enthusiastically embraced the archbishop.” Then they went to the Peoria Country Club for a luncheon with 150 special guests. Then they spent the afternoon together at Glen Oak until they left for the Coliseum.

Roosevelt stressed in his talk the Catholic contribution to the development of the United States. He predicted that eventually there would be a Catholic president. In no other country in the world do Catholics and Protestants get on so well together, each treating the other on the basis of our common citizenship. Toward the end he spoke personally about Spalding. “Let me say publicly how much I owe to him and how much assistance he has given which no one but himself could render.”

Three years later, encouraged by the Spalding Council of the Knights of Columbus, he had one last celebration in 1913 in this cathedral, the Golden Jubilee of his ordination to the priesthood.

Two thrones were placed in this sanctuary: one for the new Bishop Edmund Dunne, his successor, and one for Archbishop Spalding who presided at the Solemn Pontifical Mass.

Archbishop James Quigley of Chicago offered the Mass and Archbishop John Glennon of St. Louis spoke.

“I have no fear in placing Archbishop Spalding . . . as the one Catholic who has best understood the American Mind. He has understood it because in all where it was best, it was his own. He has understood it, because he has approached the study in a broad, generous and Catholic way. And knowing it, he did not fear it, and because of his love of it, and because it was his duty, he would instruct and elevate it, he would Catholicize it.

“In season and out of season, he struggled with voice and pen ‘to edify, enlighten and conquer for Christ’ the hearts and minds of his countrymen.

“The impression that he has made and the good that he has accomplished were unequaled in the annals of our American church and they would remain in their unfading richness at once his consolation and his crown.”

In short, he was as John Tracy Ellis called him, the American Educator.

TO ETERNITY 100 YEARS AGO

Then on Aug. 25, 1916, one hundred years ago today, John Lancaster Spalding passed to eternity. Thousands of tributes came from around the world.

One from Pope Pius X stating that it was because of him that America had its Catholic University of America.

One came from TR at Oyster Bay. “There was no finer citizen in this country, nor a man who represented better what all good Americans should wish to see in their religious leaders than Archbishop Spalding. He was a cultured gentleman and one of the most eminent and patriotic citizens in the United States .”

In this cathedral on Aug. 29, 1916, Bishop Dunne celebrated the Pontifical Requiem High Mass. Archbishop George Mundelein preached. He praised the deceased prelate “whose voice from this pulpit has so often thrilled you and fanned to brighter flame your love for God and for your country.” Mundelein called Spalding a militant churchman, a patriotic citizen, a famous educator, a powerful orator and one of the greatest essayists our country has produced.

Mundelein concluded that it was strange that he had just come from the “distant east” (New York), to pay the last farewell to Peoria’s first citizen. But then, he added, it was fitting for Spalding belonged not to this city, this diocese, this state alone but to the entire land where American Catholics had claimed him as their own. Millions had been proud of him and when Mundelein was a tiny boy it had been impressed on his memory that one of the greatest prelates of America’s church was Bishop Spalding of Peoria.

In the Latin liturgy there is an absolution at the end of the Requiem Mass. Spalding had five, the last being that of Archbishop Mundelein. Then his remains were solemnly taken to St. Mary Cemetery for burial.

Today as we remember the life of this outstanding American Educator and celebrate the restoration of this great cathedral, let us thankfully remember the legacy of the Ark and the Dove — our religious freedom now embedded in our Constitution.

Let us thank God for the Carrolls and the Spaldings, especially John Carroll, the first bishop of the United States, and John Lancaster Spalding, the first bishop of Peoria.

Let us too salute all our bishops: John Lancaster Spalding; Peter J. O’Reilly, auxiliary bishop to Spalding; Edmund Dunne; Joseph Schlarman; William Cousins; John Franz; Edward O’Rourke; John Myers; and Daniel Jenky, who has supervised this restoration.

Echoing Archbishop John Ireland in this very sanctuary, some years ago, I say to you, Bishop Jenky, on behalf of all of us here, ad multos annos!”

This is truly the day the Lord has made, let us rejoice and be glad.